This is an extended version of content that appears in the Emerging Technologies feature in the April issue of CLP.

Researchers at the University of Washington are working to develop a handheld, paper-based device that could detect infectious diseases using samples collected and tested at the point of care. Requiring no complex instrumentation, the multiplexable and disposable autonomous nucleic acid amplification test system has initial targets of drug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and influenza. The technology could hold promise for pathogen identification in remote areas, as well as densely populated areas such as hospitals, prisons, and military bases.

Led by Paul Yager, PhD, former chair of bioengineering at the University of Washington, the team comprises UW research assistant professor Barry Lutz, PhD; UW biochemistry professor David Baker, PhD; Oregon State University senior research assistant professor Elain Fu, PhD; and researchers from Seattle Children’s Hospital, Epoch Biosciences, PATH, and GE Global Research. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has provided an 18-month, $9.6 million grant after first awarding $4 million in 2011. The National Institutes of Health has also provided a $5.7 million grant to improve detection of influenza.

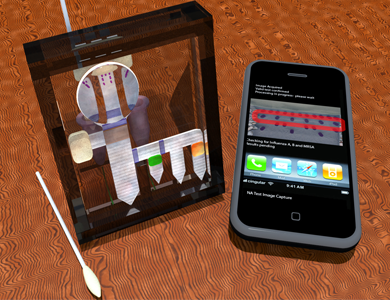

The University of Washington’s paper-based device uses a cell phone to transmit results to a clinical laboratory for testing.

Known by Yager and his colleagues as a “two-dimensional paper network,” or 2DPN, the test relies on nucleic acid amplification that activates when the substrate is exposed to specimens via a nasal swab. In less than an hour, a pattern of colored dots will appear to indicate the presence of certain pathogens. Users can then photograph and transmit the results via cell phone, while a medical professional or software at the other end interprets the pattern and issues a therapy recommendation. The researchers aim to make the technology as cost-effective, widely available, and user-friendly as a pregnancy test. Such “pocket diagnostics” could provide broad access to complex diagnostics that are currently the exclusive purview of clinical laboratories.

“The inexpensive disposable paper device combined with the cellphone as the only ‘permanent’ instrument is a really powerful combination for changing how we do medicine here and in the developing world,” Yager said. “We will move the data, not the people.”

Though testing will eventually expand to tuberculosis, sexually transmitted diseases, and other viral infections, Yager anticipates the technology may also have applications in the realms of food safety, testing for plant and animal diseases, and environmental testing for biological warfare agents.