In a field already marked by remarkable breakthroughs, advances continue unabated

By Gary Tufel

There have been remarkable breakthroughs in personalized medicine, and the advances continue unabated. Accounts of the achievements brought about by personalized medicine approaches seem to be just about everywhere.

Arthur L. Beaudet, MD, professor and chair of molecular and human genetics at the Baylor College of Medicine, says he is seeing how genomic testing and sequencing is beginning to have an impact on how physicians approach treating rare disorders.

In a recent interview, Beaudet told MedScape that genetic testing began having an impact on his field through newborn screening. When newborn screening came along, he says, physicians went from doing only phenylketonuria screening to testing for dozens of rare disorders, many of which can be managed starting at birth.

Still, for most patients who would walk in with disabilities, he and his colleagues did not know what the underlying problem was. Now, with copy-number variation analyses and genome sequencing, Beaudet says doctors can get a very specific understanding of what is going on in about 50% of the patients that they see with rare disorders.

Beaudet calls that “a dramatic increase” from around 10% a decade ago, and he sees that number improving so rapidly that soon he and his colleagues “will be able to know precisely which gene or genes are involved” in a great many of the cases they see.

In another account, an article in the May 2014 issue of Science described harnessing a person’s own immune system to fight cancer. The story was about the treatment of a 43-year-old woman with an advanced and deadly type of cancer that had spread from her bile duct to her liver and lungs, despite chemotherapy.

“Researchers at the National Cancer Institute sequenced the genome of her cancer and identified cells from her immune system that attacked a specific mutation in the malignant cells. Then they grew those immune cells in the laboratory and infused billions of them back into her bloodstream,” wrote Denise Brady in The New York Times.

Steven A. Rosenberg, MD, PhD, senior author of the article and chief of the surgery branch at the cancer institute, said that the tumors “melted away.”

Brady cautioned that the woman is not cured and that her tumors are shrinking, but not gone. But she says the report is noteworthy because it describes an approach that may also be applied to common tumors in other parts of the body that cause more than 80% of the 580,000 cancer deaths in the United States every year.

And, lest there should be any doubt, in the May 4, 2014, issue of the Vancouver Sun, staff writer Randy Shore declared that whole-genome sequencing “has officially entered the medical mainstream and kicked off an era of truly personalized medicine.” In his article, Shore discussed how Illumina is now selling high-throughput sequencing equipment that will deliver a patient’s entire genetic blueprint for about $1,000. That’s down from about $2.7 billion for the first human genome just 11 years ago.

“Whether the technology can reduce healthcare costs depends on how we choose to use the information and whether the targeted treatments promised are affordable,” Shore wrote.

Shore quoted Brad Popovich, chief scientific officer of Genome British Columbia, as foreseeing a time in the not-too-distant future when all babies will have their genome sequenced at birth, much as is now done with blood tests for a handful of common and rare diseases. This opens the way for targeted therapies or lifestyle changes that patients can take to modify the risk. But, Popovich cautions, people given information about their genetic risk for disease tended not to change their lifestyle, diet, or even stop smoking, according to several recent studies of patient behavior.

NOT ALL NEWS IS GOOD

Despite reported achievements, however, there have been problems. Last November, FDA sent genetic testing company 23andMe a warning letter because it said the firm was marketing the 23andMe Saliva Collection Kit and Personal Genome Service without marketing clearance or approval, in violation of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. FDA ordered the company to stop the sale of direct-to-consumer genetic tests, saying that 23andMe had failed to prove the validity of its genetic tests, and gave the company 15 days to respond and identify the steps it would take to address these concerns, raising questions about the clinical usefulness of genomic screening.

And there’s concern that Illumina’s above-mentioned $1,000 sequenced human genome, performed on the company’s HiSeq X10 sequencer, would also require genomic counseling in order to be used therapeutically, which would raise the cost of the service to around $17,000. In fact, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine recently found that although profound diagnostic and treatment advances can be made utilizing genome testing, significant challenges must be overcome before this sequencing can be routinely clinically useful.

Specifically, the Stanford research analyzed the whole genomes of 12 healthy people, using sequencing platforms by Complete Genomics and Illumina. They found that the machines failed to detect a sizable percentage of genes linked to inherited diseases. Also, professional genetic counselors or informatics specialists needed to study the genome up to 100 hours to provide accurate and meaningful information to patients. Considering this and the $17,000 cost, the researchers deemed the technology as not ready for general use.

THE REIMBURSEMENT HURDLE

Such a conclusion inevitably leads to the issue of reimbursement, which is the biggest issue in personalized medicine for a lab trying to develop new products and enter the market with them, says Scott McGoohan, JD, vice president for reimbursement and scientific affairs at the American Clinical Laboratory Association. It’s a three-tiered problem encompassing coverage, coding, and reimbursement, he says, and R&D costs are very high.

Personalized medicine tests are more complex, addressing the complexity of disease biology, according to David Brunel, CEO of Biodesix, which develops products for clinical decision-making and patient care. “Personalized medicine tests often have multiple markers and use algorithmic techniques to better calibrate a patient’s condition. And while the answers may not be complete, they do help physicians make better decisions about patient care and treatment,” he says.

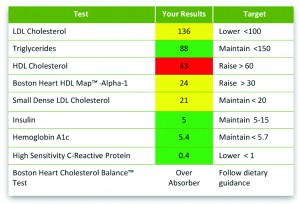

Susan Hertzberg, president and CEO of Boston Heart Diagnostics Corp, agrees that reimbursement is a big hurdle to the development and use of such ground-breaking tests. Some payors will pay for certain diagnostic tests and some don’t, deeming the procedure investigational. “There’s no rhyme or reason to this, and it’s a significant issue. Laboratory diagnostics represent about 3% of the healthcare dollar, yet inform 70% to 80% of clinical decisions, offering high value at low cost,” Hertzberg says.

Hertzberg sees the Affordable Care Act as an improvement in patient empowerment, noting its focus on prevention. But paying for it remains an issue. Spending money on diagnostics and prevention can help avoid future costs, but insurance companies don’t know whether they will be covering the patient for the long term. So they focus on reducing costs now. “Maybe now that preconditions are no longer a factor in coverage, that might change, but it hasn’t yet,” Hertzberg says.

BEYOND ONCOLOGY

Genetic and molecular tests can be used not only to diagnose diseases and conditions in patients, but also to guide drug and dosage determinations, helping patients to avoid being prescribed the medications to which they are genetically predisposed to react poorly. Until recently, the best known personalized medicine applications have been in the oncology space, with tests that are able to predict a patient’s response to various types of chemotherapy or other drugs, and the patient’s risk of cancer recurrence. However, the applications for such tests stretch far beyond oncology, in such other areas as cardiology, women’s health, and even depression and mental health conditions.

Brunel notes that much of the recent activity in personalized medicine is coming in such areas as oncology, women’s health, cardiology, and arthritis. “Most, but not all, is good work.” While Biodesix is focused on oncology, he says it will ultimately move beyond that and get involved in other disease areas, such as metabolic disorders like diabetes, focusing on better earlier interventions and better patient management. Such chronic diseases are having a significant impact on costs, and better tools are necessary. Brunel also sees a need in many other areas, such as autoimmune diseases and even dementia. “These areas are poised for significant advancement in practice if we can dial in genomics, gene expression, proteomics, and other techniques. But we can’t advance without investment in innovation, so predictable reimbursement is essential,” he says.

Biodesix currently produces VeriStrat, a clinically validated serum test for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients that helps physicians determine if a patient should receive treatment with a drug called erlotinib, an epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor (EGFRI). The test identifies patients who are likely to have good or poor outcomes after treatment with EGFRIs. VeriStrat requires only a simple blood draw and can be performed on all advanced NSCLC patients. In addition, test results are returned in less than 72 hours, allowing physicians to make quick treatment decisions, Brunel says. And Biodesix is currently validating the clinical utility of VeriStrat in other solid tumors (colorectal, pancreatic), and with novel targeted therapies.

The VeriStrat serum test for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer helps physicians determine whether a patient should receive treatment with erlotinib, an epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor.

“Metastatic lung cancer is seldom cured, but we can improve and extend the quality of life for those who have it. With VeriStrat we’re trying to outrun the tumor, and if we can get a better look at it, we can increase the patient’s life span and lower the toxicity of the drugs they take. It’s an emerging paradigm that needs to be implemented sooner rather than later,” says Brunel.

One example McGoohan notes is in the field of pharmacogenomics, in which a patient’s individual genetic characteristics can determine how that patient responds to drugs. “When a doctor is treating a patient for depression, bipolar disorder, and other psychiatric disorders, there are a number of different drugs available in several different drug classes, including atypical antipsychotics and selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors. Pharmacogenomic testing can help a clinician determine which drug will work best in which patient, and help avoid drugs with severe side effects to which the patient may be predisposed.” Targeting these patients with the correct drug for them individually is important because of the loading period—it takes 2 months before these drugs take effect and thus for it to become apparent whether the drugs are working or not, and if they have negative side effects.

Though these tests are having a significant impact in the clinical setting, personalized medicine diagnostics still account for less than 1% of testing volume in the Medicare program, McGoohan says. “These are esoteric tests, which have volumes far less than the most frequently performed routine lab tests.”

“In the Medicare program, payment rates are strictly resource-based, but don’t take into account the real value of these diagnostics, and it’s having a chilling effect. This approach is penny-wise and pound-foolish because the cost of these diagnoses is relatively low compared with the cost of treatment,” says McGoohan.

“PRECISION” OR “PERSONALIZED” MEDICINE?

Is there another, better term for personalized medicine? Some feel that “precision medicine” is more accurate, but according to ACLA’s McGoohan, both terms (and “individualized medicine”) are virtually synonymous. “Each of these terms are driving at the same concept, which is the customization of healthcare, with medical decisions and treatments tailored to the specific genetic and biochemical characteristics of the individual patient,” he says.

And it’s important to make the distinction between personalized medicine and companion diagnostics, notes Hertzberg. The latter ensures that the individual gets the right drug at the right dose based on his or her test results. Personalized medicine, however, should have a broader agenda, better identifying risk, and improving health outcomes.

Boston Heart Diagnostics provides patients with recommended dietary targets based on their test results and food preferences.

Boston Heart, which was recently granted a prestigious New York State Department of Health clinical laboratory permit for diagnostic testing, does both: next-generation diagnostics that enable the healthcare provider to better assess, treat, and manage an individual’s risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD)—and patient engagement—helping them in a positive, proactive way to make lifestyle changes that can prevent or reverse disease, Hertzberg says.

Hertzberg, who was previously with Quest Diagnostics, says many of the larger diagnostic labs are slow to change, but there’s a great need to make results more understandable to patients, thus improving health literacy, a first step in preventing or reversing diseases, driving adherence with treatment strategies, and ultimately improving outcomes. That’s not happening with old-style medical models, she says. “Everyone understands that prevention is important, but it can be hard to prove in terms of dollars and cents. But there’s plenty of evidence that prevention is not only good for patients, it’s the only logical path that will save the healthcare system money as well.”

For more information, see the sidebar “New Genomic Products and News” and the online-exclusive companion articles, “Reimbursement and the Search for ROI” and “Personalizing Cardiology.”

Gary Tufel is a contributing writer for CLP. For further information, contact chief editor Steve Halasey via [email protected].