Efforts to combat emerging and antibiotic-resistant diseases get a government boost

By Gary Tufel

For clinical labs, new insights into the origins and spread of emerging infectious diseases are helping to guide and clarify new lab practices. Energized by the ebola outbreak in West Africa and related incidents among patients treated in the United States, laboratorians have become active participants in developing and executing public policies designed to stop emerging infectious diseases in their tracks.

But it’s not just ebola that’s causing major health concerns about infectious diseases, and it’s not just laboratorians who are engaged in the fight. Healthcare policymakers at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and elsewhere throughout the world are working hard to address the vast international scope of the infectious disease issue. And along the way, they are also redefining the important roles that clinical and public health labs play in executing public policies for travel screening, quarantines of travelers from specific regions, monitoring of high-risk travelers, and more.

ROUTINE PRECAUTIONS

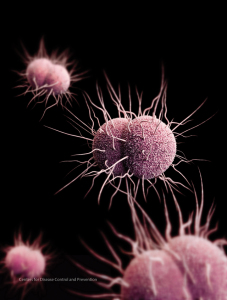

Antibiotic-resistant Campylobacter threatens the safety of human food supplies. Illustration courtesy CDC.

The risks are very real. The European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Disease (ESCMID)—an organization that explores risk assessment, knowledge sharing, and best practices in the fight against infectious diseases—has warned that Britain and Europe collectively could face more than a million deaths in an impending “antibiotic Armageddon,” unless more is done to develop new cures, faster diagnostics, and preventive measures to combat the spread of drug-resistant diseases.1

ESCMID experts issued the warning in mid-April, ahead of the society’s annual conference, held in Copenhagen April 25–28, adding that without reductions in the inappropriate use of existing antibiotics, and more money being spent on developing new drugs, deaths across Europe from drug-resistant diseases could pass the grim milestone of a million by 2025. In Britain alone, an estimated 10,000 people die each year from drug-resistant diseases, and experts at ESCMID fear this number could triple, or even quadruple, within the next 10 years.

Treatment has been greatly complicated by the emergence of so-called “superbugs,” strains of bacteria that are resistant to several types of antibiotics. According to CDC, each year in the United States these drug-resistant bacteria infect more than 2 million people and kill at least 23,000.

Equally troubling is the potential for new infectious diseases to emerge from animal populations in genetically modified forms that make them highly transmissible among humans. Worldwide, agriculture, veterinary, and health authorities are turning to genomic studies to detect and track such zoonotic pathogens before they infect human populations. Among many such infectious disease challenges is an ongoing outbreak of an avian flu named H5N2, which is spreading through poultry farms in parts of North America and forcing poultry producers in many states and provinces to kill off millions of chickens and turkeys. According to the Vancouver Sun, scientists in British Columbia are fast-tracking a genomic surveillance system for the virus.2

According to CNBC, by the end of April more than 50 cases of avian flu had been reported across multiple states, with more than 6.5 million chickens and turkeys destroyed. Both Wisconsin and Minnesota declared states of emergency to deal with the epidemic.3,4

But the risk that a highly infectious strain of H5N2 will infect humans is low at this time, according to Alicia Fry, MD, MPH, a medical officer and leader of the influenza prevention team at CDC’s national center for immunization and respiratory diseases. Speaking in April at CDC’s annual epidemic intelligence service (EIS) conference, Fry added that the H5N2 virus infects turkeys and chickens but is different from previous flu strains that have been able to infect humans. So far, she noted, it has not caused infections in humans anywhere in the world.5

Still, CDC is taking routine precautions that include trying to develop a vaccine against the H5N2 virus that could be used in humans, should it ever be needed.

The conference showcased recent groundbreaking and often life-saving investigations by CDC disease detectives. EIS officers presented their research findings from US and international-based investigations conducted over the past year and shared details of investigations that placed them in the thick of some of the world’s most challenging public health events. CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD, MPH, opened the conference with remarks and attended several sessions throughout the week.

RAPID POINT-OF-CARE TESTS

“Global infectious diseases continue to burden our healthcare system, putting pressure on regulatory agencies, healthcare providers, clinical labs, and suppliers of diagnostics and therapeutic products,” says John J. Sperzel III, president and CEO of Chembio Diagnostic Systems, Medford, NY.

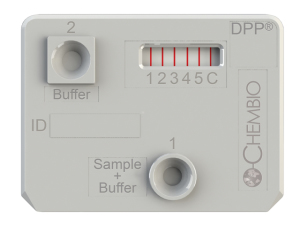

“The new paradigm in diagnostics is ‘think globally, act globally,’” says Sperzel. “At Chembio, we utilize our patented dual path platform (DPP) technology to develop rapid point-of-care tests for a number of emerging and infectious diseases such as dengue fever, ebola, hepatitis C, HIV, malaria, and syphilis. One of the unique aspects of the DPP technology is its ability to test for a number of diseases on a single device using a single patient specimen.”

Chembio’s DPP technology platform cassette showing multiplexing. It provides rapid point-of-care tests for a number of emerging and infectious diseases on a single device with a single patient specimen.

“Chembio is working with some of the brightest people and most reputable organizations in the world, having signed research agreements with CDC and with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation,” says Sperzel. “Our goal is to bring high-quality point-of-care tests to help in the effort to combat these global diseases.”

INCREASING LAB PROTECTIONS

How important is the lab’s role?

“Ebola public policy is focusing on the lab,” says Timothy Bowers MT(ASCP), CIC, director for infection prevention and control with the Inspira Health Network, Woodbury, NJ, and a member of the communications committee for the Association of Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC).

Recent ebola incidents have had lasting effects on infection prevention efforts everywhere in the hospital, including the lab, says Bowers. “In some instances, small satellite labs or point-of-care testing have been instituted immediately adjacent to treatment areas in order to prevent as much contamination as possible. Every patient seen in healthcare settings is now screened for travel abroad, using specific questions designed to ensure the safety of front-line providers.”

Because of the impact that ebola can have, observes Bowers, CDC has developed new practice recommendations not only for clinical practitioners but also for lab professionals dealing with patient specimens.6 “Previously, samples sent routinely to the lab would have been received, tested, and discarded appropriately,” says Bowers. “But now, they are first analyzed for their risk of exposing the lab to a deadly infectious disease.

“The CDC document is thorough and thoughtful in its efforts to increase protection for laboratorians,” he adds. “These recommendations have brought focus to the work we do as laboratorians and the risks we face every day.”

One aspect of the new policies that affects both labs and the healthcare sector as a whole is the need to fund emergency preparedness stockpiles and activities. “On occasion, grants are available to offset the costs of some emergency preparedness activities,” says Bowers, “though it has been my experience that the grants never quite equal out to the cost of performing these exercises correctly.”

Increased lab costs specific to emergency preparedness can be seen in point-of-care sites and satellite labs having higher costs per test than the main lab, says Bowers. “We are careful to rotate routinely purchased items through our stockpile and to keep specialty items to a minimum,” he adds. “Working closely with purchasing, materials management, or others in charge of an institution’s purchasing and inventory management is key to reducing the impact these additional expenditures have on the institution.”

In 2014 APIC presented testimony about the US government’s response to the 2014 ebola disease outbreak to the US Senate committee on appropriations. The association’s message to the committee was that the 2014 ebola outbreak dramatically reinforced the need for strong protocols and procedures to prevent infection within US healthcare facilities.7

“But what has not been clearly articulated is that our current infection prevention and control infrastructure is already being pushed to the limit in order to address day-to-day activities needed to prevent healthcare-associated infections,” states the APIC testimony. “Nearly 75,000 people die each year with these infections—about twice the number who die from automobile accidents.”

Personal protective equipment and regulated air flows prevent pathogen exposure in a CDC biosafety level 4 lab. Photo by James Gathany courtesy CDC.

In October 2014, APIC undertook a survey that dramatically underscored the absence of an overall infection prevention surge capacity in US healthcare facilities, and illustrated the pressing need for greater resources devoted to infection prevention.8 The survey of more than 1,000 infection preventionists in US acute care hospitals found that only 6% of hospitals feel well-prepared to receive a patient with the ebola virus.

Moreover, 50% of hospitals have just one—or less than one—full-time equivalent infection preventionist on staff. As ebola preparedness demands intense, in-person training led by infection prevention experts, facilities must have sufficient personnel to address other infection prevention needs as well. For many healthcare facilities, the lack of adequate infection prevention staff means that preparing for an ebola incident will occupy the full attention of all qualified staff, thereby reducing the facility’s ability to address any other immediate crisis and to prevent the spread of infections. (For more information, see the companion article, “American Society of Microbiology Takes Action.”)

These survey responses are especially troubling, notes the APIC testimony, given what we know about the dangers of healthcare-associated infections.

APIC is active in promoting legislation to combat ebola and other infectious diseases. More information is available on the organization’s Web site at www.apic.org/advocacy/federal-legislation.

NATIONAL PLAN TO COMBAT ‘SUPERBUGS’

Antibiotics have been a critical public health tool since the discovery of penicillin in 1928, but the emergence of drug resistance in bacteria is reversing the gains of the past 80 years. Many important drug choices for the treatment of bacterial infections are becoming increasingly limited, expensive, and, in some cases, nonexistent. The loss of antibiotics that kill or inhibit the growth of bacteria means that quick and reliable treatment of rare or common bacterial infections—including bacterial pneumonias, food-borne illnesses, and healthcare-associated infections—can no longer be taken for granted.

Health authorities fear that the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains of Neisseria Gonorrhoeae may make gonorrhea virtually untreatable. Illustration courtesy CDC.

“Antimicrobial resistance” encompasses resistance against drugs used to treat infections, and may arise in many different types of pathogens, including bacteria, viruses (eg, influenza and the human immunodeficiency virus), parasites (eg, the parasitic protozoa that causes malaria), and fungi (eg, Candida spp.). Bacteria with antibiotic resistance result from mutations or from the acquisition of new genes that reduce or eliminate the effectiveness of antibiotics.

While all of these pathogens are dangerous to human health, the resistance of bacteria to antibiotics is the single most crucial obstacle to treating infectious diseases. On March 25, the White House unveiled the US government response to this impending crisis: a $1.2 billion, 5-year national action plan focused on eliminating “superbug” resistance in bacteria that present an urgent or serious threat to public health.9

The plan would nearly double the amount of federal money allocated to the fight. It calls for creating a “one-health” approach to testing and reporting superbugs around the country, as well as establishing a DNA database of resistant bacteria. New, rapid tests to detect emerging resistant bacteria will be developed, and research for new antibiotics and vaccines will be accelerated.

The plan provides a roadmap for implementing the national strategy for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria and addressing the policy recommendations of the president’s council of advisors on science and technology. Although the plan’s primary purpose is to guide US government activities, it is also designed to guide action by public health, healthcare, and veterinary partners in a common effort to address urgent and serious drug-resistant threats that affect people in the US and around the world.

“The United States will work domestically and internationally to prevent, detect, and control illness and death related to infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria,” states the plan, “by implementing measures to mitigate the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance, and ensuring the continued availability of therapeutics for the treatment of bacterial infections.”

Gary Tufel is a contributing writer for CLP. For further information, contact CLP chief editor Steve Halasey via [email protected].

REFERENCES

- European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Disease. Antibiotic Armageddon in UK and Europe by 2025: ESCMID warns that Europe may surpass one million deaths due to ineffective antibiotics by 2025. April 21, 2015. Available at: www.escmid.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/2News_Discussions/Press_activities/ECCMID_2015/ESCMID_one_million_deaths_UK_consumer.pdf. Accessed April 27, 2015.

- Shore R. New genome project to identify avian flu hot spots in Fraser Valley. Vancouver Sun, April 14, 2015. Available at: www.vancouversun.com/health/genome+project+identify+avian+spots+Fraser+Valley/10969360/story.html. Accessed April 27, 2015.

- Polansek T. Wisconsin declares state of emergency over bird flu in poultry. CNBC, April 20, 2015. Available at: www.cnbc.com/id/102602966. Accessed April 27, 2015.

- Huffstutter PJ. Minnesota declares state of emergency over bird flu in poultry. CNBC, April 23, 2015. Available at: www.cnbc.com/id/102616374. Accessed April 27, 2015.

- Steenhuysen J, Davis M. Risk low for human infection from US strains of bird flu. Reuters UK, April 22, 2015. Available at: http://uk.reuters.com/article/2015/04/22/us-health-birdflu-cdc-idUKKBN0ND2L520150422. Accessed April 27, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance for US laboratories for managing and testing routine clinical specimens when there is a concern about ebola virus disease. March 19, 2015. Available at: www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/healthcare-us/laboratories/safe-specimen-management.html. Accessed April 27, 2015.

- Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology. Testimony of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC) to the US Senate Committee on Appropriations on the US government response to the 2014 ebola virus disease outbreak. November 7, 2014. Available at: www.apic.org/Resource_/TinyMceFileManager/Advocacy-PDFs/Senate_Ebola_Testimony_FINAL.pdf. Accessed April 27, 2015.

- APIC ebola readiness poll: results of an online poll of infection preventionists. Washington, DC: Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, 2014. Available at: www.apic.org/Resource_/TinyMceFileManager/Topic-specific/Ebola_Readiness_Poll_Results_FINAL.pdf. Accessed April 27, 2015.

- National action plan for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Washington, DC: The White House, 2015. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/national_action_plan_for_combating_antibotic-resistant_bacteria.pdf. Accessed April 27, 2015.